The causes and consequences of the hunger crisis in World War I

Food shortages in World War heightened social inequality

The early 20th century was a time of huge economic growth. German industry expanded, more and more people were able to find work in the cities and per-capita income rose. Agricultural production was not able to keep pace with this rapid development, however, and the state relied on imports to feed the population.

When World War I broke out, supply shortfalls soon became apparent. Forty percent of the male population was conscripted, which drew a great deal of labor away from the land. The Allied blockade of German ports intensified the situation. Prior to 1914, Germany had imported one third of its foodstuffs and half of its animal feed.

Hunger and its impact on height

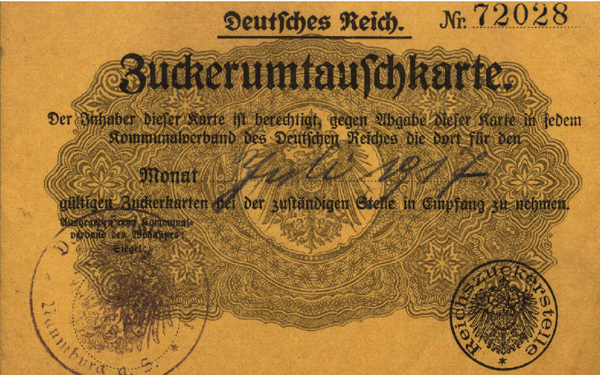

To ensure that the population got enough to eat, the authorities began to ration food and limit prices from 1916. People were still going hungry, however, as Dr. Matthias Blum of TUM’s Chair of Agriculture and Food Economics explains: “Average body weight in Germany declined from 60 kilograms in 1914 to 49 kilograms in 1917. Over this period, grain production roughly halved while meat production came to a near standstill.”

The situation was particularly acute in 1916 and 1917, when adults had to survive on 1,000 calories per day on average. This corresponds to just 50 to 60 percent of a person’s daily nutritional needs. For children born during the war years, this malnutrition prevented them from reaching their full growth potential.

But as Blum discovered, the impact varied significantly from one socioeconomic group to another. When these children became adults, there was a height difference between the upper and middle class of around 1.7 centimeters and the same between the middle and lower class. “Differences in height were already noted before the war – but they became more pronounced in the war years,” Blum explains.

Rise of the black market

The researcher points to unequal access to food as the reason behind this height discrepancy. “In spite of bread and meat rationing, there just was not enough food to go around. In addition, price ceilings canceled out the production incentives that had been introduced for farmers. As a result, between a third and a half of all foodstuffs were sold illegally on the black market – at prices which only wealthy families could afford.” The government was therefore not able to deliver on its commitment to distribute the burden of war evenly across society.

It would appear that the food shortages of World War I were also the result of poor decision-making. For example, to secure crops of potatoes as food for the people, the government ordered the slaughter of millions of pigs. “This caused the price of meat to soar, with the result that farmers, and even city-dwellers, started to rear pigs illegally and feed them with other staple foodstuffs like grain,” Blum adds. To rein in the high price of meat, the authorities eventually approved the reintroduction of pig farming.

Blum based his study on data from almost 5,000 soldiers who served in World War II. The Third Reich mobilized most of the young male population and recorded the address, father’s occupation, health and height of all recruits.

Publication:

War, food rationing, and socioeconomic inequality in Germany during the First World War, Matthias Blum, The Economic History Review, DOI: 10.1111/j.1468-0289.2012.00681.x

Contact:

Dr. Matthias Blum

Technische Universität München

Lehrstuhl für Agrar- und Ernährungswirtschaft

Tel.: +49 8161 71-2773

matthias.blum@tum.de

aew.wzw.tum.de