RNA-based gene regulation with dynamic proteins

Shaping up to make the cut

Ribonucleic acids – RNAs for short – serve as intermediates in the ordered translation of the hereditary information stored in the DNA into blueprints for the synthesis of specific proteins. In the cell nucleus, defined segments of the DNA are first transcribed into RNA copies called messenger RNA precursors (pre-mRNAs).

In many cases, these primary transcripts contain interspersed sequences that interrupt the actual protein-coding sequence. These “introns” must be removed and the coding sequences spliced before the information can be used for protein synthesis.

Indeed, a given gene may encode for several different forms of a protein by a process called alternative splicing, which plays an important role in post-transcriptional gene regulation – for differently spliced mRNA strands code for different protein forms that may also differ in their function. All splicing operations are carried out by a complex molecular machine in the cell nucleus, which is referred to as the spliceosome.

Researchers led by Professor Don Lamb at the Department of Chemistry at LMU and Professor Michael Sattler (Helmholtz Zentrum München und Technical University of Munich (TUM)) have now shown that the distinct structural configurations adopted by a protein which is essential for assembly of the spliceosome on mRNA precursors have a critical influence on splicing efficiency.

Protein dynamics influence biological function

The spliceosome found in human cells is made up of many different subunits, which must be assembled onto the mRNA precursor in a series of carefully choreographed steps. The binding specificity of individual subunits is crucial for both spliceosome assembly and function.

“The assembly factor we have studied, called the U2 Auxiliary Factor or U2AF for short, is critical for the correct recognition of the splicing sites at one end of the introns,” says Lena Voithenberg, first author of the new paper.

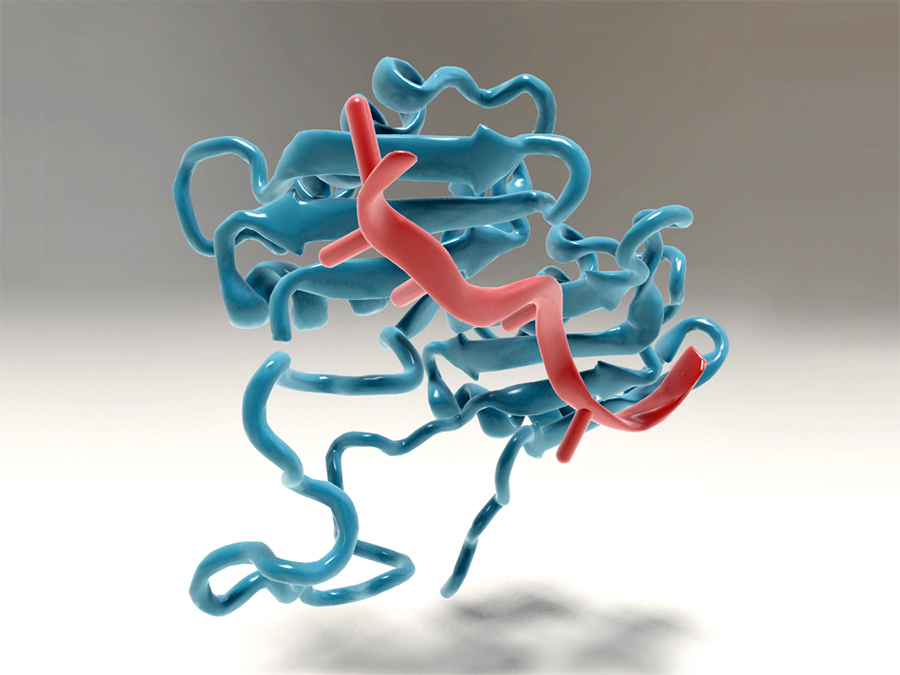

U2AF itself is made up of two different subunits. In its free form, the larger of the two is a highly dynamic protein, as Voithenberg and her colleagues demonstrated by means of single-molecule fluorescence microscopy.

Experiments using nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy carried out in parallel at the Bavarian NMR Center (BNMRZ) (run jointly by the Helmholtz Zentrum München and the TUM) provided further information relating to the structure and conformational dynamics of U2AF.

“We found that the large subunit rapidly switches its conformation from an open to a closed structure on timescales of micro- to milliseconds,” Voithenberg explains, but only the open form can bind to the RNA.”

Moreover, the proportion of molecules in this conformation depends on the relative binding affinity of the RNA sequences available: Sequences that show a high affinity for the binding subunit therefore have a higher probability of being recognized – and cleaved – than those with a lower affinity.

Structural arrangement regulates splicing efficiency

According to the Munich researchers, their results suggest that the different structural arrangements adopted by the large subunit of U2AF serve to regulate the splicing efficiency at different splicing sites. This in turn has obvious implications for how mRNA precursors are cleaved and spliced, which in turn affects not only the structure of the final protein, but also the rate at which it is synthesized.

The correct regulation of alternative splicing plays a central role for many cellular processes, and errors in splicing contribute to cancer and many genetic diseases. Understanding the molecular basis of splicing is a starting point to develop innovative therapies for these diseases in the future.

The work was funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG) via the Clusters of Excellence Center for Integrated Protein Science Munich (CIPSM) and Nanosystems Initiative Munich (NIM), the SFB 1035, the Graduate Program 1721 and the Emmy Noether Program. The project was further supported by the Center for NanoScience and the BioImaging Network of the LMU, the Bavarian Molecular Biosystems Research Network of the Bavarian Ministry of Science and the Austrian Science Fund (FWF).

Publication:

Recognition of the 3' splice site RNA by the U2AF heterodimer involves a dynamic population shift;

Lena Voith von Voithenberg, Carolina Sánchez-Rico, Hyun-Seo Kang, Tobias Madl, Katia Zanier, Anders Barth, Lisa R. Warner, Michael Sattler and Don C. Lamb; PNAS Early Edition, Oct., 31, 2016 – DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1605873113

Contact:

Prof. Dr. Michael Sattler

Technical University of Munich

Chair of Biomolecular NMR Spectroscopy

Lichtenbergstr. 4, 85748 Garching, Germany

Tel.: +49 89 289 13418 – E-mail – Web